Cocaethylene

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | benzoylecgonine ethyl ester, ethylbenzoylecgonine, |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Produced from ingestion of cocaine and ethanol |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.164.816 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H23NO4 |

| Molar mass | 317.385 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

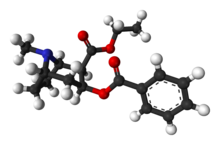

Cocaethylene (ethylbenzoylecgonine) is the ethyl ester of benzoylecgonine. It is structurally similar to cocaine, which is the methyl ester of benzoylecgonine. Cocaethylene is formed by the liver in small amounts when cocaine and ethanol coexist in the blood.[1] In 1885, cocaethylene was first synthesized (according to edition 13 of the Merck Index),[2] and in 1979, cocaethylene's side effects were discovered.[3]

Metabolic production from cocaine

[edit]Cocaethylene is the byproduct of concurrent consumption of alcohol and cocaine as metabolized by the liver. Normally, metabolism of cocaine produces two primarily biologically inactive metabolites—benzoylecgonine and ecgonine methyl ester. The hepatic enzyme carboxylesterase is an important part of cocaine's metabolism because it acts as a catalyst for the hydrolysis of cocaine in the liver, which produces these inactive metabolites. If ethanol is present during the metabolism of cocaine, a portion of the cocaine undergoes transesterification with ethanol, rather than undergoing hydrolysis with water, which results in the production of cocaethylene.[1]

- cocaine + H2O → benzoylecgonine + methanol (with liver carboxylesterase 1)[4]

- benzoylecgonine + ethanol → cocaethylene + H2O

- cocaine + ethanol → cocaethylene + methanol (with liver carboxylesterase 1)[5]

Physiological effects

[edit]Cocaethylene increases the levels of serotonergic, noradrenergic, and dopaminergic neurotransmission in the brain and has a higher affinity for the dopamine transporter than cocaine, but has a lower affinity for the serotonin and norepinephrine transporters.[6][7] These pharmacological properties make cocaethylene a serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI; also known as a "triple reuptake inhibitor").[8]

Although it cannot be bought, cocaethylene is largely considered recreational in and of itself, with stimulant, euphoriant, anorectic, sympathomimetic, and local anesthetic properties with a longer duration of action than cocaine.[9][10] A 2000 study by Hart et al. on the effects of intravenous cocaethylene in humans found that "cocaethylene has pharmacological properties in common with cocaine, but is less potent," consistent with prior research.[9]

Risks

[edit]While cocaethylene is more dangerous when administered alone, research suggests that the increase in risk from combining cocaine and ethanol is "thought to be due to alcohol decreasing the metabolism of cocaine and, therefore, increasing [...] cocaine concentrations with only a minimal (if any) contribution to an increased risk from the formation of cocaethylene".[11]

Some studies[12][13] suggest that consuming alcohol in combination with cocaine may be more cardiotoxic than cocaine and "it also carries an 18 to 25 fold increase over cocaine alone in risk of immediate death".[10]

See also

[edit]- Ethylphenidate

- Euphoriants

- Methylvanillylecgonine

- Local anesthetics

- RTI-160

- Stimulants

- Tropanes

- Vin Mariani

- Pemberton's French Wine Coca

References

[edit]- ^ a b Laizure SC, Mandrell T, Gades NM, Parker RB (January 2003). "Cocaethylene metabolism and interaction with cocaine and ethanol: role of carboxylesterases". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 31 (1): 16–20. doi:10.1124/dmd.31.1.16. PMID 12485948.

- ^ Jones AW (April 2019). "Forensic Drug Profile: Cocaethylene". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 43 (3): 155–160. doi:10.1093/jat/bkz007. PMID 30796807.

- ^ * Doward J (8 November 2009). "Warning of extra heart dangers from mixing cocaine and alcohol". The Guardian.

- ^ "MetaCyc Reaction: 3.1.1". Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ "MetaCyc Reaction: [no EC number assigned]". Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ Jatlow P, McCance EF, Bradberry CW, Elsworth JD, Taylor JR, Roth RH (August 1996). "Alcohol plus cocaine: the whole is more than the sum of its parts". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 18 (4): 460–464. doi:10.1097/00007691-199608000-00026. PMID 8857569.

- ^ Perez-Reyes M, Jeffcoat AR, Myers M, Sihler K, Cook CE (December 1994). "Comparison in humans of the potency and pharmacokinetics of intravenously injected cocaethylene and cocaine". Psychopharmacology. 116 (4): 428–432. doi:10.1007/bf02247473. PMID 7701044. S2CID 6558411.

- ^ Marks D, Pae C, Patkar A (December 2008). "Triple Reuptake Inhibitors: The Next Generation of Antidepressants". Current Neuropharmacology. 6 (4): 338–343. doi:10.2174/157015908787386078. PMC 2701280. PMID 19587855.

- ^ a b Hart CL, Jatlow P, Sevarino KA, McCance-Katz EF (April 2000). "Comparison of intravenous cocaethylene and cocaine in humans". Psychopharmacology. 149 (2): 153–162. doi:10.1007/s002139900363. PMID 10805610. S2CID 25055492.

- ^ a b Andrews P (1997). "Cocaethylene toxicity". Journal of Addictive Diseases. 16 (3): 75–84. doi:10.1300/J069v16n03_08. PMID 9243342.

- ^ "Cocaine Powder: Review of the evidence of prevalence and patterns of use, harms, and implications" (PDF). UK Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Retrieved 14 March 2025.

- ^ Wilson LD, Jeromin J, Garvey L, Dorbandt A (March 2001). "Cocaine, ethanol, and cocaethylene cardiotoxity in an animal model of cocaine and ethanol abuse". Academic Emergency Medicine. 8 (3): 211–222. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01296.x. PMID 11229942.

- ^ Farré M, de la Torre R, Llorente M, Lamas X, Ugena B, Segura J, Camí J (September 1993). "Alcohol and cocaine interactions in humans". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 266 (3): 1364–1373. doi:10.1016/S0022-3565(25)39392-4. PMID 8371143.

Further reading

[edit]- Morris J (19 April 2010). "Cocaethylene: responding to combined alcohol and cocaine use". Alcohol Policy UK.

- Landry MJ (1992). "An overview of cocaethylene, an alcohol-derived, psychoactive, cocaine metabolite". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 24 (3): 273–276. doi:10.1080/02791072.1992.10471648. PMID 1432406.

- Hearn WL, Rose S, Wagner J, Ciarleglio A, Mash DC (June 1991). "Cocaethylene is more potent than cocaine in mediating lethality". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 39 (2): 531–533. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(91)90222-N. PMID 1946594. S2CID 36163843.

- Hearn WL, Flynn DD, Hime GW, Rose S, Cofino JC, Mantero-Atienza E, et al. (February 1991). "Cocaethylene: a unique cocaine metabolite displays high affinity for the dopamine transporter". Journal of Neurochemistry. 56 (2): 698–701. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb08205.x. PMID 1988563. S2CID 35719923.